Lothar, mz-forum.com

Electrics of

MZ two-stroke

(with additions to the four-stroke Rotax models from

MZ)

Vers.

2015-11-11

Vers.

2015-11-11

Table of Contents

Foreword .................................................

.................................................. .......... 5

0. Preliminary remarks

0.1 Required (electrical) aids

............................................ ...................... 7

0.2 Terms, symbols

..............................................

............................................ 7

0.3 Important terminal designations for vehicle

electrics ...................................... 8

0.4 Measurement of voltage, current and

resistance with a digital multimeter ........ 9

A DC generator and 6V electrical system

A.1 Field-regulated DC alternator for 6 V

vehicle electrical system ........................ 11

A.1.1 Checking the winding

resistances

A.1.2 Alternators - function

test

A.2 Electromechanical controller (6 V)

......................................... ....................... 16

A.2.1 Mechanical adjustment

A.2.2 Electrical adjustment

A.3 Electronic controller (6 V)

......................................... .................................. 26

A.3.1 Removal of the regulator

resistor

A.3.2 Electronic controller -

function test

A.4 Contact ignition system (6 V)

..........................................

..................................... 29

A 4.1 Overview

A.4.2 Contact, ignition

capacitor

A.4.3 Ignition coil

A.4.4 Ignition cable, connector

and plug

B Three-phase generator and 12 V electrical

system

B.1 Field-regulated three-phase alternator for

12 V vehicle electrical system ......................... 37

B.1.1 Checking the winding

resistances

B.1.2 Alternators - function

test

B.1.3 The field winding fuse 2A "slow"

B.2 Rectifier block

..............................................

............................................ 41

B.2.1 Circuit

B.2.2 Function test

B.3 Electromechanical controller (12 V)

......................................... ...................... 44

B.3.1 Mechanical adjustment

B.3.2 Electrical adjustment

B.4 Electronic controller (12 V)

......................................... ................................. 49

B.4.1 Replacement of electromechanical

by electronic plus regulator

B.4.2 Function test for

electronic plus controller

B.4.3 Rectifier / electronic

minus regulator on the last 2T models

B.4.4 Function test of

rectifier / electronic minus regulator

B.5 Ignition system (12 V)

..........................................

.............................................. 56

B.5.1 Contact ignition system

B.5.2 Electronic ignition

system with Hall sender

C Permanently excited 12 V three-phase

generator (Rotax)

C.1 Three-phase generator -

function test ............................................ ................ 60

C.2 Rectifier / controller

block - function test .......................................... .......... 62

C.3 Electronic tachometer (eDZM) ..........................................

............. 64

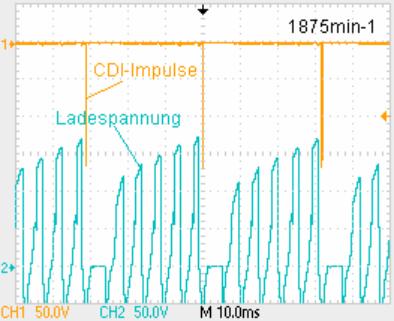

C.4 Electronic ignition (CDI, Nippondenso)

........................................ ......... 65

V Miscellaneous

V.1 Cable connections

..............................................

.......................................... 67

V.1.1 Cable resistance and voltage drop

V.1.2 Voltage drops in the vehicle electrical

system

V.2 Accumulator

..............................................

.................................................. ... 71

V.2.1 Characteristic values and

properties

V.2.2 Function test

V.2.3 Check operating conditions in the vehicle

electrical system

V.4 Some typical error patterns

............................................ ............................. 80

V.4.1

Battery is not sufficiently charged, engine cuts out when idling

V.4.2 Charge

control does not go out or is glowing

V.4.3

Ignition fails

V.5 Horn

..............................................

.................................................. .............. 83

V.6 Electronic tachometer

............................................. ........................ 87

V.7 The setting of the breaker ignition

........................................... ........... 91

V.8 Vehicle light bulbs

............................................

........................................ 98

Z Appendix

Z.1 Circuit of the electronic 6

V regulator MZ ELEKTRONIKUS ................ 101

Z.2 Electronic

controller for permanently excited Rotax-LiMa

............................. 102

Z.3 P ermanent-excited LiMa with rectifier /

regulator and ignition .................

103

Z.3.1 Regulator / rectifier for

2-phase LiMa

Z.3.2 Electronic ignition (CDI,

similar to vape)

Z.3.3 Rotax: Electronic ignition (CDI,

Nippondenso)

Z.4 12V regulator circuit L

9480 in the ETZ ....................................... .......... 112

Z.4.1 Properties of the L9480 control circuit

Z.4.2

Measurements on the L9480 circuit

Z.4.3 Installation in the vehicle electrical system and behavior

Z.5 Battery chargers and their properties

........................................... ...... 121

Z.6 Electronic flasher unit 12V (FER GmbH) ........................................

..... 126

Z.7 Ignition

position: conversion from (° before TDC) to (mm before TDC)

......................... 128

Bibliography

.................................................

.....................................

131

Preface

In this text, important components of the vehicle electrics of the MZ

two-stroke engines up to 1989 are described with regard to their function and

testing. Some topics relating to the electrics of the four-stroke Rotax models

have also been included. The purpose of this document is to provide “help for

self-help” when analyzing malfunctions or adjusting or repairing them. To do

this, however, a minimum of electrical engineering and / or metrological

knowledge is required, which can easily be acquired as an educated and willing

MZ driver even at an advanced age. However, if there is an insurmountable

aversion to anything electrical, it is better to keep your hands off it.

The representations are basically structured in such a way that each

assembly can be tested independently of the rest of the on-board electrical

system. One or the other section may also help to better understand the

operation of certain electrical devices in the vehicle.

You can improve your own skills if the tests,

measurements or adjustments described are first tried out on functioning

components. Perhaps there is a rectifier plate, an alternator or a regulator in

the spare parts box, which can be used as objects for practice measurements

without causing damage.

The specification of data, inspection, measurement and test methods

often goes beyond the scope known from the literature, in that a number of

missing or inaccurate information has been replaced by measurement or empirical

values obtained by the "young vehicle electrician"

without information such as "sufficiently large", "usual"

or "sufficiently small" to leave in the dark. In this respect, small

adjustments will probably not be missing here and there in the future. Since

there are no technological documents from the production period from which the

target parameters of the product development at that time could be read,

measurements had to be carried out on individual objects for some information

in the hope that these would meet the typical values.

The author is therefore happy to receive any critical or additional

information, suggestions for improving or expanding the information. Where is

something written incomprehensibly or not clearly formulated? Confirmatory

reports of measurements are also welcome. The more that comes together in this

way, the more secure the information becomes.

Ultimately, the long-term, interested follow-up of electrical problems

in the Internet forum for MZ drivers gave the impetus for this presentation of

selected electrical problems on two-stroke MZs. Error descriptions of helpless

MZ drivers, collective remote diagnostics, factual and belief discussions as

well as valuable hints and advice from Foristi that I received, expanded and

deepened the electrical knowledge about our MZs, which is certainly not

possible without the Internet on this scale would.

I therefore dedicate this work to the MZ forum: www.mz-forum.com

Anyone who has found the

tips and hints listed here helpful in solving problems can return the favor

with a donation for running the forum server. Information is available on the

portal page of

www.mz-forum.com.

Exclusion of liability: No liability whatsoever is accepted for damage caused

by the practical implementation of the instructions.

If the rights of third parties

have been unknowingly violated, this must be reported immediately so that the

corresponding content can be removed.

The work or the content

may

·

Given to the author (Lothar, mz-forum.com) are made publicly

available (in the WWW is only the link allows the source through which the

always current version can be reached:

http://pic.mz-forum.com/lothar/ELEKTRIK/MZ-Elektrik.pdf)

not allowed

· Be used for commercial purposes

not allowed

·

Edited, modified or changed in any other way

Lothar, November 23, 2015

0.

Preliminary remarks

0.1

Required (electrical) tools

·

3 ½ digit digital multimeter , eg HP-760B

·

Various 6 V or 12 V car

light bulbs as test equipment or as a replacement for loads.

·

Adjustable voltage

source 0-15V / 0-3A, e.g. Peaktech 6080

In some cases a fixed voltage source is

sufficient, eg an external 6 V or 12 V battery or the on-board battery itself. The

specified device can also be used as an ideal battery charger due to the

continuously adjustable voltage and current limitation.

0.2

Terms, symbols

Nominal voltage in the 12 V on-board voltage

system: 13.2 V.

corresponding to the 6 V on-board

voltage system: 6.3 V.

(the service life specification of vehicle

light bulbs in ECE R37 relates, for example, to this nominal voltage)

LiMa = Abbreviation for alternator or voltage

generator

Ground = electrical reference point on the motor

housing (D-) or at a central ground point of the wiring harness.

Circuit symbol for ground connection: (for MZ applies: ground = negative

pole)![]()

Unless otherwise specified, voltages are

always measured against ground.

General direct or alternating voltage source (e.g. mains-operated voltage

supplies, batteries or accumulators), polarity indication by +/- or arrow

orientation:

Special: electrochemical DC voltage source (battery, accumulator)

0.3

Important terminal designations in vehicle electrics

(1) Ignition coil to the break

contact

(15/54) Switched

positive lead from the ignition light switch / brake light

(30) Battery plus (even after a

fuse, if present)

(31) Battery minus (even after a

possibly existing fuse),

equivalent to mass

or D-

(31b) Switched ground to the horn

(49) Input of a two-pole flasher

unit (plus side)

(49a) Output of a two-pole flasher

device (minus side)

(51) Controller output to battery

plus (sometimes also referred to as B + )

(56a) high beam

(56b) low beam

(58) Tail light, parking light

(61) LiMa-side connection of the

charge indicator light

D + Positive pole of the direct

current LiMa or positive terminal after

Three-phase

rectifier

D- Negative pole of the direct

current LiMa, generally also for the designation

the vehicle mass

used

DF + external connection of the

excitation field winding to the controller

often plus

controlled systems only as DF referred

DF- second end of the field

winding, in plus-regulated systems in the

LiMa clamped to

ground

U, V, W Connection terminals of the three-phase

LiMa

B + controller output after

battery plus for electronic controllers,

corresponds to (51)

0.4

Measurement of voltage, current and resistance with a digital multimeter

Usual

designation of the input sockets

COM:

Connection of the minus measuring cable

VΩmA:

Connection of the (plus) measuring cable for voltage [V], resistance [Ω] or current

measurement [mA]. The additional label "FUSED 200mA MAX" means

that the current measuring path is internally fused with 200 mA to

protect the device.

UNFUSED 20Amax:

Connection of the measuring cable for current measurement in the range from 200

mA to 20 A. The device is not protected in this area, exceeding the maximum

current (here eg 20 A) will destroy the device.

Safety rule: Always start measurement with the

largest measuring range!

Voltage

measurement

The voltage is

measured in the unchanged system between two selected contact points. The point

to which the COM cable leads is used as the reference point for the displayed

polarity of the voltage value. COM is preferred connection for ground. If you

swap the measuring cables, the same numerical value is displayed for the

voltage, only with the opposite sign.

Common errors:

a) If the fused current

input socket was accidentally used for an intended voltage measurement, the

internal fuse of the device usually blows

, which often goes unnoticed for a long time!

b) If AC voltage is

incorrectly measured in the DC voltage range, the display is always close to

zero.

Current

measurement

To measure the

current , the line in which the current to be measured flows must be

disconnected. This is expediently done at a connection point.

If the multimeter

fuse has blown , zero is always displayed for the current!

Resistance

measurement

For resistance

measurement , the element must be separated from the system by at least one

connection , otherwise incorrect measurements will occur.

Special

measurement problems

Measurement

of very high resistances (> 10 kΩ): Do not bridge the

measurement connections with your fingers during the measurement, because the

parallel body resistance falsifies the result.

Measurement

of very small resistances (<10 Ω): Before the

measurement, bring the ends of the measuring cables together and read the value

(lies in the range of 0 .0.5 Ω). The

correction value determined in this way must then be subtracted from each

measured value. If the measuring cables are exchanged, the correction value

must be determined again.

Measurement

of the smallest resistances (<10 mΩ): A known

current is sent through the resistor - if possible - and the voltage drop is

measured directly (!) At the resistor. The value is calculated as R = U / I.

For illustration: measuring current 1A, measured 1 mV results in R = 1 mV / 1 A

= 1 mΩ.

Fidgeting display or implausible

values with digital multimeters

Digital measuring

devices are usually more nimble than analog pointer instruments. This can lead

to short interference pulses (e.g. from the ignition) being detected and causing the display values to jitter. For

this reason, the measuring lines should generally be routed as far away as

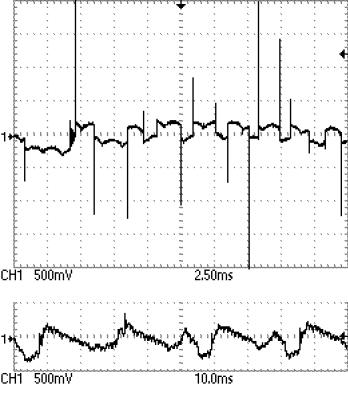

possible from cables and ignition equipment. With DC voltage measurements, a

ballast as shown below can help in stubborn cases. Interfering frequencies>

30 Hz are thus suppressed. If this is not enough, the capacitor can be

increased (e.g. 10 times the value). The larger the capacitor, the more

effective the suppression of voltage fluctuations, but the slower the response

of the display.

DC voltage filter as ballast

Such malfunctions do

not normally occur in vehicles with an intact electrical system. It is

therefore important not to be satisfied with eliminating the symptoms, but to

look for the causes of the interfering impulses. The following are to be

examined: spark plug connector (internal flashovers), ignition capacitor (ineffective),

collector (grooves, nicks, scaling) or slip rings (breakouts), regulator

contacts (burn-off), loose contacts / broken cables, fuse contacts (corrosion).

A DC

generator and 6 V electrical system

A.1

Field-regulated DC alternator for 6 V vehicle electrical system

A.1.1

Checking the winding resistances

Before the LiMa is tested with the motor

running, the winding and insulation resistances should be checked (for

setpoints, see Table A.1-3). Since the measurement of very small or very large

resistance values harbors particular risk of error, the

instructions in Section V.3 must be observed.

If slightly higher values occur

with certain rotor positions, sanding the copper lamellas with 500 grit

sandpaper often helps.

If the rotor continues to turn, it is possible

that the multimeter display goes "crazy". This has to do with the

fact that the residual magnetism induced when the rotor moves a voltage that

confuses the resistance measurement. The reading is only to be taken when the rotor

is at a standstill!

The actual insulation resistances are mostly

over 20 MΩ.

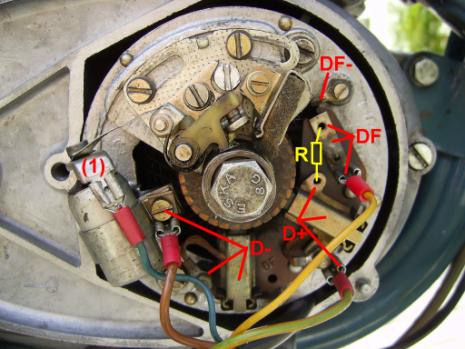

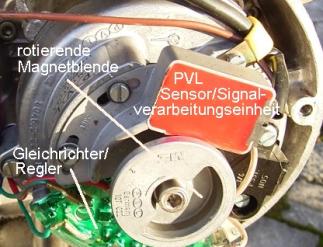

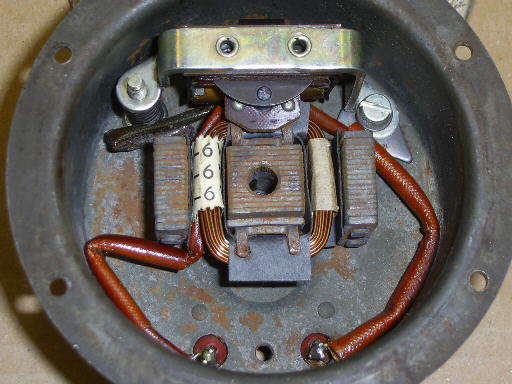

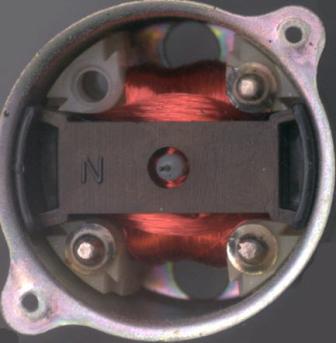

Fig. A.1-1: 6 V / 10 A / 60 W DC generator of

an ES150, exciter series resistor R has been removed (yellow symbol R)

|

Test

object |

Measurement

conditions |

Resistance

measurement between |

LiMa 6 V / 60 W. |

LiMa *) 6 V / 30 W. |

|

Rotor- winding |

Loosen the

copper wire of the minus carbon Loosen the

D + cable Loosen the

D + side connection from R. Slowly turn

the rotor 360 ° during the measurement so that all segments of the collector

are checked. |

D + and

loosened copper braid of the minus coal |

(0.2 ± 0.2) Ω |

(0.8 ± 0.2) Ω |

|

Rotor- isolation |

- ditto - |

D + and

ground |

> 1 MΩ |

> 1 MΩ |

|

Field- winding |

DF + sided Loosen

connection from R. Loosen the

DF cable Loosen the

DF winding end from the ground |

DF + and

DF- |

(1.7 ± 0.3) Ω |

(2.6 ± 0.3) Ω |

|

Field- isolation

|

- ditto - |

DF + and

ground |

> 1 MΩ |

> 1 MΩ |

|

R. |

Both

connections solve from

R. |

|

(4.5 ± 0.5) Ω |

unavailable |

|

R insulation |

- ditto - |

any Connector

and metal body |

> 1 MΩ |

unavailable |

Table A.1-3: Setpoints for winding and

insulation resistances

*)

LiMa 6 V / 30 W for RT125 / 0-2

Definition

of "plus or minus regulation" for vehicles with a negative pole on

the chassis according to [5]

In the plus-regulated

LiMa , the plus- side field winding connection (DF +) is led to the

controller connection (DF).

The minus-side field winding connection (DF-)

is connected to ground (D-) (see Figure A.1-2a). If an excitation field series

resistor R is available, it is connected between D + and DF.

With the minus-regulated

LiMa , the minus- side field winding connection (DF-) is led to the

controller connection (DF).

The positive-side field winding connection (DF

+) is connected to D + (see Figure A.1-2b). If an excitation field series

resistor R is available, it is connected between DF and D-.

A.1-2: Alternator, electrical block

diagram

DF- negative

end of the field winding,

DF + positive end of excitation field winding

DF controller

connection for field winding

R series resistor for field winding

(not applicable when using electronic

controllers)

D + positive

collector carbon brush (short: plus

carbon)

D- negative

collector carbon brush (short: minus carbon) = ground

The excitation field series resistor R is often designed as an external resistor

(see Fig. A.3-1), but it can also be used in the excitation field winding

itself (e.g. RT125 / 3 series partially) or in the electro-mechanical

controller (e.g. IFA RT 125 ) be integrated.

Plus and minus rules are of equal importance , they have neither advantages nor

disadvantages in relation to the other type of circuit. There are also no

differences in terms of the magnetic or electrical polarization of the LiMa.

If the winding ends of the excitation field

winding are accessible, a minus-regulated LiMa is created by reconnecting the

field winding connections to a plus-regulated one and vice versa. If it is a

field winding in which the excitation field series resistor is integrated

(feature: 3 connections emerge from the stator), it is no longer effective

after the conversion, so that an external resistor must be provided.

If the control type is specified, this has an

impact on the design of the controller. The plus regulator must

"send" a positive current into the DF + connection so that the

generator voltage increases, the minus regulator must "pull out" a

positive current from D- to achieve the same effect. As a visual comparison,

imagine a tube with a suction pump connected to the left in the first attempt

and a pressure pump to the right in the second attempt. The liquid flows

through the tube in the same direction in both cases, but the pumps are of

different construction.

All MZ two-stroke engines are plus-regulated,

the exceptions are the BK350 and the last series ETZs (around 1990) with a

regulator circuit.

With the RT125 / 3 there are irritations

as to whether the plus or minus control was originally intended or whether a

changeover occurred during series production. Separate controller types would

then be required for plus and minus regulations. So far, only plus-regulated

systems could be found in RT125 / 3 vehicles that had been checked in practice

and were apparently in their original condition.

It can therefore be assumed with a very high

degree of probability that the RT125 / 3 is generally plus-regulated .

The cause of this confusion is possibly an

error in the circuit diagram of the RT125 / 3, which is in the original

operating instructions and which is also found in other publications. The error

can even be found in the diagram on the inside of the bobbin case cover. The

exciter field series resistor is incorrectly drawn in parallel to the field

winding, which makes no electrical sense.

A.1.2

Alternators - function test

If the resistance

measurements according to A.1.1 do not show any irregularities, the LiMa can be

tested with the engine running. All cables (D +, DF +) leading to the

controller must be disconnected and secured beforehand. In this test, a fault

in the rotor (e.g. winding short) can be detected if the voltage at D + does

not reach the orientation value mentioned above.

Fig.

A.1-4: LiMa

test circuit with external excitation

After connecting the

battery, the 6 V lamp lights up and a current of around 1.8 A is impressed into

the field winding. The engine is now started normally (on battery ignition) and

the voltmeter is observed. If the speed is higher than idle, the generated DC

voltage must quickly rise to 10 ... 12 V with an intact LiMa and the 12 V lamp

connected as a load lights up. If the 18 W incandescent lamp is removed, the 60

W lamp goes out regardless of the speed.

Caution: Do not

increase the equivalent speed beyond 12 V, the light bulb can burn out!

To be on the safe

side, if all previous measurements and tests were successful, the

self-excitation can still be checked. To do this, all lamps are disconnected

when the motor is at a standstill and a wire bridge is inserted between DF +

and D +. The engine will start again. A voltage of 12 ... 15 V must be

generated at a slightly increased speed. Incidentally, this situation

corresponds to the push-on position of the ignition light switch. However,

since the controller is not effective in this test, it should last a maximum of

10 s in order not to overload the field winding.

Self-excitation

requires a sufficiently large residual magnetism in the iron core of the

windings. If this has been lost or there is a magnetic reversal of polarity

(e.g. if the LiMa has been stored in the earth's magnetic field for a long

time), it can be assumed that sufficient residual magnetism will remain after

the function test described above has been carried out.

The magnetization or

magnetic correct polarity can, however, also be brought about a little more

aggressively by bringing the positive terminal of the battery (unsecured!) Into

contact with D + for a moment (0.1 s).

A.2

Electromechanical controller (E / M, 6V)

A.2.1

Mechanical adjustment

The structure of the electromechanical voltage

regulator was kept almost unchanged from the first RT in 1950 to the 12 V

systems of the ETZ series of the 1990s. Deviations can be found in the details,

e.g. in the mechanical design of the bending elements.

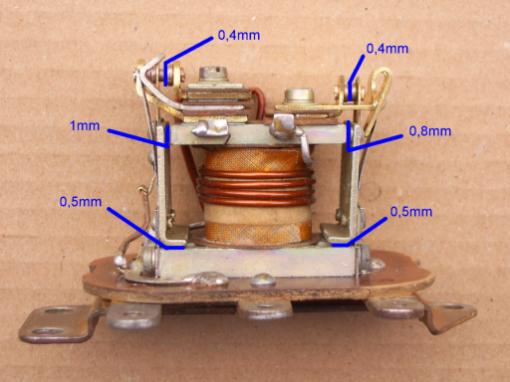

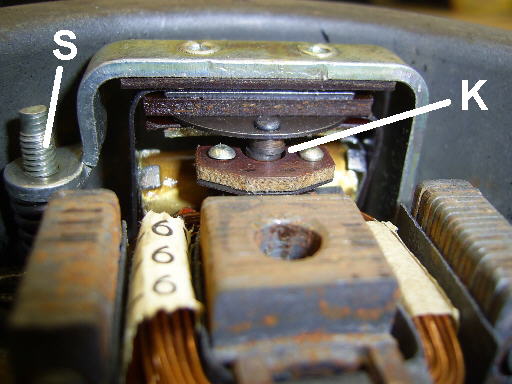

Figure A.2-1: Designation of the contacts and setting elements on the

electromechanical

Controller, older on the left, newer on the

right

In the literature [1] and [2] you can find

different adjustment measures. Based on this information, sensible orientation

values have been set in Figure A.2-2 (blue entries).

Control of the mobility of the

contact anchor plates

First it is checked whether the contact tongues

can be pressed easily up to the core without the angled lower ends of the

contact anchor plates sitting on the core foot. In the relaxed state, a

dimension of 0.5 mm is given in [1]. If nothing sticks, nothing should be

changed in the current distance, even if the value is not exactly 0.5 mm!

Setting the controller contact (left

side)

The setting of the magnetic gap (1 mm) and the

controller contact spacing (0.4 mm) takes place in one step, as both fixed

contacts can be moved after loosening the upper cylinder head screws. The

magnet gap (1 mm) is set by moving the left fixed contact and the contact

distance (0.4 mm) by moving the right fixed contact.

Fig. A.2-2:

Orientation values for the distances to be set

Image A.2-3: Determination of the gap width with existing aluminum rivets

in the contact anchor plate

This attitude requires skill and patience. And

it has to be right in the end when the cylinder head screws are tightened

again! If you hit the target values within ± 0.1 mm, you can be satisfied.

Setting the reverse current contact

(right side)

Magnet gap (0.8 mm) and contact distance (0.4

mm) are also set simultaneously after loosening the corresponding cylinder head

screws. The contact distance (0.4 mm) can be set with the left fixed contact. Here,

too, a setting accuracy of ± 0.1 mm should be aimed for.

Note

As soon as mechanical changes are made to the

controller, changes to the electrical setting values are to be

expected, so that subsequent electrical adjustment is absolutely necessary!

A.2.2

Electrical adjustment

The connection

sequence applies to older controllers (see Fig. A.2-1) with screw connections:

51 DF D

+ / 61

The plug contact

version has the following sequence:

DF D +

61 51

where D + and 61

have separate contact lugs, but are connected to one another. The ground

contact is on the base plate of both controller versions.

Fig.

A.2-4:

(a)

Functional diagram of the electromechanical regulator for the 6V / 60W

generator.

(b)

Regulator of the 6 V / 30 W LiMa for the RT125 / 0-2 with integrated field

winding series resistor

Preliminary

test of the controller with the help of resistance measurements

(unused connections

remain open)

The resistance of

the voltage coil R SSP was determined from our own

measurements on several copies of 6 V / 60 W regulators with different

production dates. The last measured coil resistance with 10 Ω was

marked 3/76 and the first with 20 Ω was marked 4.80. The conversion must therefore

have taken place between 1977 ... 1980.

The reason for this

could be a desired reduction in the wire cross-section of the voltage coil. In

addition to saving copper, this also reduced the controller's power consumption

from around 5 W by 50% to 2.5 W.

Before the

measurement, the contacts must be cleaned with a strip of hard, transparent

drawing paper (parchment), otherwise the small contact resistances of 0.2 Ω and less are hardly

achievable!

|

element |

Resistance Measurement between the connections |

condition

|

Value

for Regulator of 6V / 60W- LiMa |

Value for Regulator of 6V / 30W LiMa RT125 / 0 ... 2 |

|

Voltage coil |

D + / 61 and mass |

|

R SSP |

R SSP (10 ± 0.5) Ω |

|

Controller contact |

D + / 61 and DF |

Rest position Middle position pressed on |

0 ... 0.2 Ω infinite R SSP |

0 ... 0.2 Ω R V (7 ± 0.5) Ω R SSP

// R V (4 ± 0.5) Ω |

|

Controller contact |

Dimensions and DF |

Rest position Middle position pressed on |

R SSP infinite 0 ... 0.2 Ω |

R SSP (10 ± 0.5) Ω R SSP + R V (17 ± 0.5) Ω 0 ... 0.2 Ω |

|

Reverse current contact |

D + and 51 |

Rest position pressed on |

infinite 0 ... 0.2 Ω |

infinite 0 ... 0.2 Ω |

Table

A.2-5:

Setpoints for resistance measurements on the controller.

R SSP :

voltage coil resistance up to the end of the 1970s: (10 ± 0.5) Ω from the beginning of the 1980s: (21.5 ± 1) Ω,

R V :

field winding series resistor

Notes on

measuring the RT125 / 0-2 controller relay when it is removed

On the rear side

(inside the coil box) the lead out connection corresponds to terminal 51. On

the front side of the regulator relay (facing outwards in the coil box) there

are 3 wire connections. DF is the first connection that leads to the middle

contact spring of the controller contact. DF must be connected to the second

connection coming out of the winding! Ground comes as a third connection from

the inner fixed regulator contact. D + is to be connected to the bottom of the

metallic core of the coil former. If the controller is measured in the coil box

on the vehicle, all cables leading to the outside must be loosened from the

screw terminals.

Electrical adjustment of the controller

Confusing

facts from the literature [2]

The information on

the electrical adjustment of the 6 V regulator in the literature [2] (see Table

A.2-6) is hardly practicable; the problem is explained below. The recommended

procedure is shown on the next page.

The information from

[2] is given in Table A.2-6. Compliance with the specified speeds can at best

be estimated for the TS and older models that do not have a tachometer.

|

Pick-up voltage reverse current contact |

6.5V ... 6.9V |

|

Drop-out voltage reverse current contact |

5.4V ... 6.2V |

|

on-board voltage to be set for N = 1800 ... 2200 min-1 and 10 A load |

6.2V ... 6.8V |

A. |

|

on-board voltage to be set for N = 4000 min-1 for continuous daylight operation

|

6.8 V ... 7.2 V |

B. |

Load

case A: low beam (40 W) + rear light (5

W) + stop light (18 W) = 63 W,

gives

a total of 10 A at 6.3 V and disconnected battery

Load

case B: Not further defined

Table

A.2-6: Voltage values for electrical adjustment taken

from the

Literature [2]

The usual load in

solo daylight mode is 40 W (low beam) + 5 W (rear light), which is around 8 A.

In addition, there is an average of 2 A for the ignition coil, which adds up to

10 A. Turn signals and stop light are consumers that usually only work for a

short time. When fully charged, the intact battery takes up almost no more

charging current. It can be seen from this that the two load cases A and B

hardly differ at all.

For the daylight

operation prescribed today, 6.8 ... 7.2 V should be set according to the table.

With a permitted 7.2 V, however, at 25 ° C one would already be at the gassing

limit of the lead-acid battery (see Section V.2). If you consider that the

setting accuracy of the mechanical regulator is often worse than 0.1 V and that

changes also occur due to wear and tear of the contacts during operation, the

battery could endure if you just hit the upper limit of the permitted range

would meet.

In addition, the

table allows the reverse current contact to be adjusted to 6.9 V in extreme

cases, but the on-board voltage comes to a maximum of 6.8 V. According to the

table, this would be permitted, but fatal, since the LiMa would then never be

connected to the on-board network or the battery.

For all of the

reasons mentioned above, sensible

setting values that

have proven themselves in practice are therefore suggested in the following

work steps .

Adjustment

and preparation procedure

The sequence of the

work steps must be strictly adhered to.

1) Adjustment of the pull-in voltage

of the reverse current contact

2) Check

the dropout voltage of the reverse current contact

3)

Voltage adjustment of the regulator contact

4)

Checking the charging voltage in the vehicle under normal operating conditions

Before setting,

clean the contacts with a strip of hard, transparent drawing paper or

parchment! In stubborn cases, sandpaper with a grain size of 500 or finer

should be used.

1) Inrush voltage of the

reverse current contact

The reverse current

contact must close when the generator voltage exceeds the typical open circuit

voltage of the battery (6.3 V). This results in a meaningful target area for

the

Pull-in

voltage of the reverse current contact: (6.4 V ± 0.1) V .

The voltage of the

controllable voltage source is slowly and continuously increased starting from

zero (measuring circuit see Fig. A.2-7) until the contact picks up (= lamp

lights up). If the tension is too low , the

associated bending element must be bent outwards in

order to increase the restoring force of the contact restoring spring or vice

versa.

Fig.

A.2-7: Circuit

for voltage adjustment

of the reverse

current contact

Since the bending elements made of aluminum or

brass become brittle after a few rough bends and can break off, you should work

very carefully and avoid unnecessary bends.

If several switching attempts are carried out

under the same conditions, the reproducibility of the switching point will

usually be poor. Experience has shown that fluctuations of ± 0.1 ... ± 0.2 V are typical. The

reasons for this are: wear of the contacts, variable residual magnetism in the

core, changes in properties due to the relay heating up during the adjustment

procedure.

2)

Check the dropout voltage of the reverse current contact

In order to control

the drop-out voltage, the reverse current contact is first closed by

increasing the voltage (= lamp lights up), whereby the voltage must be

increased further until the contact anchor plate or the aluminum rivets

are completely in contact with the core. Only now is the voltage slowly and

continuously reduced until the reverse current contact drops out (= lamp goes

out). According to the information

from [2] (see Tab.

A.2-6) the permissible range for the drop-out voltage is 5.4 ... 6.2 V. The

voltage should not be lower than 5.4 V, as the battery is then with Idle speed

increasingly against the LiMa begins to work. However, nothing can be adjusted

if the dropout voltage should be lower than 5.4 V.

3)

Voltage adjustment of the regulator contact

The measuring

circuit according to Figure A.2-8 only differs from the previous one in that the

test lamp is now connected to terminal DF. The voltage of the controllable DC

voltage source is increased slowly and continuously from zero. We observe that

the return current contact is first tightened (click), and when it is increased

further, the armature plate of the return current contact hits the core

(click). Both processes (click - click) can also take place almost at the same

time.

Fig. A.2-8:

Circuit for voltage adjustment of the regulator contact

As the voltage

increases, the brightness of the incandescent lamp increases. If the voltage is

so high that the regulator contact anchor plate is attracted, the regulator

contact opens and the bulb goes out.

Then we increase the

voltage by a further 0.3 ... 0.5 V and observe how the regulator contact moves

evenly beyond the central position in the direction of the inner fixed contact.

However, if the regulator contact armature is suddenly pulled to the core

shortly after it has been lifted off, the two fixed contacts must be pushed

outwards by a few tenths of a millimeter in parallel. To do this, loosen the

screws originally secured with paint. After this correction, the anchor plate

distance to the core is slightly larger than specified in the mechanical

presetting. Then check that the contact moves evenly beyond the central

position.

Now the switching

point of the controller contact is delicately limited by increasing or

decreasing the voltage several times (light bulb alternately "on"

<-> "off"), then measured and recorded. In an optimum

charging voltage of 6,9V plus a derivative of 0.2V (voltage drops via

cable, securing, etc.) as a set value 7.1

V sought.

If the voltage is too low , the associated bending element

of the controller contact (see Figure A.2-1) must be

bent outwards in order to increase the

restoring force of the contact restoring spring. If the

tension is too high, bend the bending element inwards

.

You should definitely get an impression of the

extraordinary sensitivity of the setting before

re-bending by tucking a piece of paper under the return spring and

observing the change in the switching voltage. Experience has shown that this

manipulation leads to value changes of up to +0.5 V depending on the thickness

of the paper strip.

Since the bending elements are made of aluminum

and become brittle and break off after repeated bending, you should absolutely

avoid unnecessary bending.

The setting of the

RT125 / 0-2 controller for the 6 V / 30 W LiMa is possible with the specified

circuit. Because of the integrated series resistor, the light bulb does not go

out at the switching point, but only becomes slightly darker. The difference in

brightness at the switching point is small and therefore more difficult to

perceive.

4)

Checking the charging voltage in the vehicle under normal operating conditions

Before checking the vehicle, make sure that the

cabling is OK and the contacts (especially on the fuses) are in good condition

in order to keep voltage drops to a minimum.

The controller is installed in the vehicle and

the engine is started. "Usual operating conditions" mean here:

Slightly increased speed compared to idling (corresponding to about 2000 ... 3000min

-1 ) and low beam on. Now the voltage is measured directly at the

battery terminals. Under normal ambient temperature conditions (15 ° C ... 25 °

C) this is 6.9 V.the desired setting value. Since a few amps of load

current (headlights, taillights, ignition, battery charge) flow through the

controller's current coil, the control voltage systematically decreases by 0.3

... 0.5 V compared to the original setting after step 3. The correction

increases higher tension values can easily be achieved by placing

strips of paper underneath the contact spring, which prevents the bending

elements from bending.

Electromechanical controllers change their

properties over longer periods of operation. It is therefore advisable to check

the charging voltage on the battery every year as described above and to

adjust it if necessary.

Electromechanical regulators do not regulate

load fluctuations ideally, so that, for example, when the low beam is switched

off, the charging voltage jumps up by up to half a volt.

Anyone who has set the regulator according to

the above regulation, but afterwards thinks that they have to do something good

for the battery by driving without the low beam, will achieve exactly the

opposite. The higher charging voltage will very likely exceed the gassing limit

of the battery and reduce its service life or even lead to destruction!

A.3

Electronic controller (6 V)

A.3.1

Removal of the regulator resistor

If the electromechanical controller is replaced

by an electronic one, it is necessary to remove the field winding series

resistor. Figure A.1-1 shows the LiMa already with the regulator resistor

removed.

It is also possible to leave the series

resistor in the LiMa and simply put it out of operation. This has the advantage

that when upgrading to an electromechanical controller, all parts are available

and you only have to reconnect. The two connecting wires of the series resistor

are screwed together under the fastening screw of the winding body foot (earth)

(see Figure A.3-1).

Fig. A.3-1:

Deactivated field winding series resistor

(both connections clamped under fastening)

If the controller in the coil box of the

RT125 / 0-2 is replaced by an electronic version, no measures are

required, as the field winding series resistor is integrated in the controller

relay and is therefore removed when it is removed. With the RT125 / 3 ,

the series resistor is located in the LiMa as usual and must be removed or

rendered ineffective.

A.3.2

Electronic controller - function test

Most electronic controllers (analog principle)

can be tested for function with the

same test circuit as was used for the electromechanical in the removed (or

"disconnected") state.

Fig. A.3-2:

Circuit for the function test

of the electronic controller

When the voltage at D + / 61 is increased, the

brightness of the lamp initially increases to the same extent. When the cut-off

voltage is reached and exceeded, the incandescent lamp goes out. In principle,

this can be done "gently", that is in the range of a few tens of mV.

The switching point is therefore determined at

medium brightness of the lamp. Since most electronic regulators use a

semiconductor diode as a non-return valve, the value of the cut-off voltage at

the switching point must be equal to the amount of the diode forward voltage

(Si-pn diodes: 0.8 V ... 1.0 V, Schottky diodes 0.4 V ... 0.5 V) higher than

6.9 V.

Cut-off voltages of 7.3 V ... 8.0 V

are therefore classified as unsuspicious.

Fig. A.3-3:

Circuit for testing the non-return valve

In case (a), the incandescent lamp must remain

dark. The reverse current displayed by the multimeter should be well

below 1 mA (typically µA range).

If one takes 1mA as the value for the diode

reverse current in the worst case , then calculated over a month this would

cause a creeping discharge of the battery of 30 x 24 hx 1 mA = 0.72 Ah and would

just be acceptable.

In case (b) the incandescent lamp lights up and

approx. 2 A flow. In this case, the multimeter shows the diode forward

voltage of the reverse current diode , which is approx. 0.8 ... 1.0

V (for Schottky diodes 0.4 .. .0.5 V).

Due to the differently designed products, when

using an electronic controller, it is very important to check the voltage on

the battery under real load and operating conditions in the vehicle after the

successful function test.

Usually nothing can be set on the electronic

controller, so that you can only find out whether the battery charging voltage

is acceptable or not (see section V.2.3 "Checking the operating conditions

in the vehicle electrical system").

In a pinch, however, which can be Controller

voltage by inserting a diode at 51 / B + to a diode forward voltage lower

. When attaching the diode, however, its

power consumption of up to 10 W must be taken into account.

A.4 Contact ignition system (6 V)

A.4.1 Overview

This section is

about checking all components of the ignition circuit for proper function. Instructions

for setting the breaker ignition can be found in Chapter V.7. The ignition

system includes the breaker contact actuated by the crankshaft cam, the

ignition capacitor, ignition coil, ignition cable, spark plug connector and

spark plug. Experience has shown that faults in the ignition system are the

most common cause of engine failure. If only one of the heavily used components

fails, the entire system fails.

A.4.2

Contact, ignition capacitor

In order to include the lead to the ignition

coil when checking the breaker contact, the cable at terminal 1 is disconnected

from the ignition coil for the duration of the measurement and the resistance

to ground is measured at the end of the cable.

(a) Contact closed: <0.1 Ω * *) Definitely measuring tips

(b) Contact open: > 1 M Ω * note in chapter V.3

It usually takes a while until a correct

resistance value is displayed for measurement (b), as the ignition capacitor

lying parallel to the contact has to be reloaded by the measuring device.

If the values do not come true,

the following causes (among others!) May be present:

(a) resistance greater than 0 , 1 Ω : corroded breaker contacts, dirty or worn out,

cable or clamping points (see Section V.1..) is defective or unreliable

(b) Resistance much less than 1 M Ω : Cable

insulation defective, capacitor has plate connection

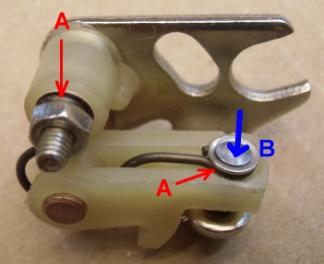

Figure A.4-1: Problem areas on the contact spring

(A) and contact riveting (B)

A more precise

assessment of the closed interrupter contact

is possible if the voltage drop between the connection lug of the capacitor and

ground is measured. When the ignition is switched on, a contact current of

approx. 4 A flows in 6 V systems, and 2.7 A in 12 V systems. The voltage drop

above the original

MZ contacts is

typically around 90 mV or 60 mV. If it is significantly larger, the 3 measures

outlined below can possibly bring about an improvement:

1) Smooth out eroded

contacts with a contact file.

The burnished wire

spring and the two contacts A (see Fig. A.4-1) cause a considerable proportion.

2) Carefully file the

wire spring eyelet under the M3 nut until it is bright or add an M3 tooth lock

washer.

3) Rivet the rivets

on the upper contact. For this purpose, the lower contact plate is placed on a

metal plate and a punch is placed on the flat head B. With a few blows, the

upper contact is slightly mushroomed and the contact resistance is reduced.

The result can be

checked by measuring the voltage drop again. If no improvements are possible,

the contact should be exchanged.

The capacitor can stand

on its own when removed

·

Isolation

(resistance> 1 M Ω ) and

·

Capacity (0.22 µF + 20%

/ -10%) can be checked.

If the capacitor values are OK at

room temperature, this does not necessarily mean that correct functioning is

guaranteed even if the temperature in the motor housing is increased. Failures

that only occur at engine operating temperature and "heal" again when

cold are possible.

In the case of defective ignition capacitors

(before 1990), for example, when heated to 100 ° C, a sharp drop in insulation resistance

(<< 1 M Ω) with a

simultaneous increase in capacitance (up to 5 times the nominal value), which

led to misfires. To heat up the capacitor for a heat measurement, immerse it

about 1 cm deep for about 5 minutes in boiling water and measure resistance ( > 1 M Ω) and capacitance (0.22 µF + 30% / -20%) immediately

after Remove. It is important to ensure that the potting gap on the housing and

on the contact does not come into contact with water, as it easily penetrates

as it cools down.

A.4.3

Ignition coil

The function of the

ignition coil is a transformer with a primary (index 1) and secondary coil

(index 2). Every technical coil is determined by its inductance L (in H) and

its winding resistance (in Ω ). The

parameters of the equivalent circuit of the 6V ignition coil were determined

and averaged experimentally on several specimens.

A.4-2:

Equivalent circuit

of a 6V ignition coil

Although there is a

series connection of resistance and inductance between terminals (1) and (15)

as well as between (15) and (K), the digital multimeter only records the

resistance because it is measured with direct current. The multimeter does not

"see" the inductance when measuring resistance, just like when

measuring winding resistances in the LiMa.

The nominal values

for winding and insulation resistances are listed in Table A.4-3.

In any case, short circuits and ground circuits as well as winding breaks can

be found.

|

element |

Measurement between |

resistance |

Approximate values

for RT125 / 0-3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ohmic resistance of the primary coil |

(1) and (15) |

(1.5 ± 0.2) Ω |

1.3 Ω |

|

Ohmic resistance the secondary coil |

(15) and K |

(7.5 ± 1) kΩ |

3.3 kΩ |

|

Insulation resistance |

(1) and housing such as (15) and housing such as (K) and housing |

> 1 M Ω each |

|

Table

A.4-3: Winding and insulation resistances of the 6V ignition

coil

Poor contact between

the ends of the windings (1) and (15) is a fault that sometimes only

appears when heated up due to sporadic misfiring. In order to improve the

contact, the contact caps of the ignition coil are unscrewed and their inner

surfaces are made bare with a fiberglass brush. The winding ends are very

carefully scratched (if the wire breaks!) Until the copper shine can be seen

(Fig. A.4-4). To counteract further corrosion, a little Vaseline grease can be

put under the caps before putting them on.

Figure

A.4-4:

Dismantled contact cap on the

ignition coil

If the resistance

values are within the tolerance, this does not necessarily mean

that the ignition coil is OK. Internal voltage flashovers can already occur in

the cold state if the properties of the insulation material have changed.

Similar to the

ignition capacitor, thermal problems often lurk in the ignition coil, which

remain hidden when measuring on the workbench when it is cold.

The reasons for this

are thermal changes in the winding and insulation properties as well as

chemical effects after penetration of moisture. In the latter case,

electrochemical elements can even form (copper winding - water - aluminum

housing). On a defective specimen, after heating, a direct voltage of up to

1000mV was found between the open terminals (1) / (15) and the aluminum

housing. If the coils are faultless, the values are well below

10mV.

Good statements can

be made with the test setup described below

Win picture A.4-4. The

circuit corresponds to a minimum ignition circuit set up outside the vehicle

(see Figure A.4-6), but instead of the spark plug, an adjustable spark gap

(ignition voltage tester) is used. The voltage source (lead battery) is

selected according to the nominal voltage of the ignition coil to be tested. Since

higher ignition voltages are generated during the test than is the case in

normal operation, higher primary voltages (up to 500V) can also occur at

terminal (1). Instead of the usual ignition capacitor, a more voltage-resistant

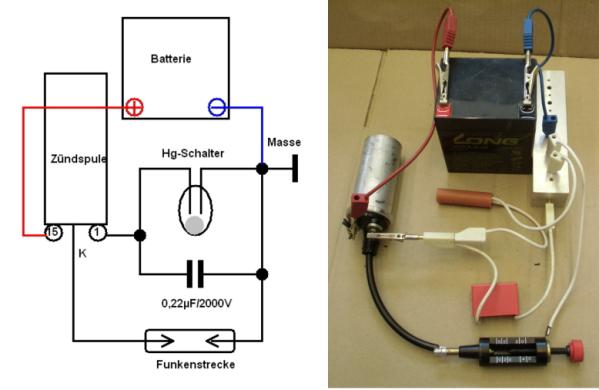

(0.22µF / 2000V) must be used.

In order to achieve

reproducible, bounce-free switching processes, the use of a mercury switch (Hg

switch, Hg tilt switch) is required. All components of the test site are

currently (2014) still available in relevant motorcycle accessories and

electronics stores. However, it is to be expected that mercury switches will

disappear from the range in the future, as has already happened with mercury thermometers. Experienced

electronics engineers can, however, also replace the Hg switch with a

voltage-proof transistor ignition.

Fig. A.4-5:

Circuit and practical structure for testing ignition coils

Safety note: In particular, people with impaired health are

strictly discouraged from operating the test station. Accidental sparkover on

any part of the body can be life-threatening.

The electrode spacing of the spark gap is

always changed when the battery is disconnected. 6 V ignition coils have a

maximum spark length of 8 ... 10mm, 12 V ignition coils 10 ... 15mm. High humidity has a strong influence on the spark length that can

be achieved. In dry air, a breakdown field strength of 3kV / mm is expected. 10mm

spark length means 30kV voltage!

The ignition coil is heated up by keeping the

Hg switch permanently closed. The heating process is carefully monitored. Excessive

heating will destroy the ignition coil. After 3 to 5 minutes, a temperature has

usually already been reached that just barely allows the housing to be touched.

The spark test is now repeated with the ignition coil warmed up. Based on

previous experience, a reduction in the maximum spark length of 20% can be

regarded as normal. If the reduction is greater, it must be assumed that the

heated ignition coil in the vehicle can cause ignition problems.

A.4.4

Ignition cable, spark plug cap and spark plug

Ignition cable

In the case of the ignition cable, lengthy

measurements will be dispensed with and if mechanical wear of the copper core

at its ends or visible corrosion can be seen, it will be replaced. If it should

nevertheless be checked: The copper core has a very small resistance, which,

within the scope of our measurement accuracy, would have to be specified as

(0.0 + 0.1) Ω . However, there are also cores

made of resistance material, whereby the cable is then supposed to take over

the function of the interference suppression resistor. The cable resistances in

conventional lengths are then in the order in which the values for suppression

resistors are, therefore, 1 k Ω to several 10 k Ω. These cables work well with our MZs if the

ignition system has no weaknesses elsewhere. If you are unsure, you can make no

mistake about replacing such a cable with one with a normal copper core.

Spark plug connector

There is usually an interference suppression

resistor (1 k Ω ... 10 k Ω ) in the plug connector . The value is

usually noted as an indication on the connector, although there are also

connectors without resistance, i.e. with zero Ω .

When measuring the continuity from the

cable-side connector input to the plug-side contact, this value must be

verifiable to ± 20%. Infinite resistance means that there is an interruption,

the plug must be replaced, even if it strangely still works, because the

interruption may be overcome by a flashover inside.

If the connector is sheathed in metal, the insulation

resistance to the sheet metal sheath must be well above 1 M Ω .

Persistent moisture at the connection points between ignition cable

- ignition coil and ignition cable - spark plug connector often leads to

ignition failure. As is well known, this happens suddenly in heavy rain or

creeping in with morning pew. Tightly fitting and non-porous sleeve sleeves

protect against this, but also keep moisture that has penetrated in for longer.

The sheet metal jacket of the candle holder is also a moisture collector in

this regard. If the "originality" does not suffer and nobody

complains about radio interference, you should remove the sheet metal covering

of the plug connector with suitable pliers.

spark plug

The candle is almost impossible to get at by

measuring it. Only the traditional method of subjectively assessing the spark

at the electrodes according to its strength helps here. It has to be strong and

bluish-white, accompanied by a clearly audible crack. One speaks of the crisp

spark ...

However, it must be taken into account that

there are high temperatures and high pressure in the cylinder, which can mean

that the candle that has passed the roadside visual test nevertheless reacts

with "spark silence" in the cylinder. Only a (really !!!) fresh

candle will help. And if it should then work satisfactorily, the most important

action is still to come, namely to actually throw away the defective candle!

Honestly, I didn't always do it consistently, and what was the result? That

at some point - all previous history is forgotten - after years you will screw

in the same cucumber again and bring yourself to the brink of despair through

your own fault.

The value of the interference

suppression resistor (s) in the ignition circuit

can vary within wide limits without adversely

affecting the proper function, whereby an overall intact ignition system is

assumed.

If the candle is weakening and moisture

has crept into the ignition cable and the battery is at the end of it,

increasing the interference suppression resistor from 0 to 100 kΩ may tip the scales, which in no way means that

the above thesis is wrong.

It even sparks with a blade of grass in the

"high resistance area" instead of the ignition cable and also

with a suppressed candle (NGK BR ...) and a suppression resistor in the

plug! The participants at the forum meeting in Sosa 2008 were able to see this

for themselves with their own eyes and ears.

Anyone who has the experience that it ignites

"noticeably" better without resistance should not be talked out of

this for the Buddha's or whose will. It is important that you have personally

gained a positive experience and are happy with it from now on. And zero point

zero ohms are not wrong either!

Minimum ignition circuit

If there is no ignition spark or if the

ignition is unreliable, it is worth setting up a "minimum ignition

circuit" as shown in Figure A.4-6. Only the absolutely necessary

components are used in order to exclude possible errors in the wiring of the

machine as well as short circuits, line breaks, fuse problems and the ignition light switch.

Figure A.4-6:

Structure of a minimum ignition circuit

As long as this structure does not work, there

is little point in looking for the fault elsewhere. If it works, however,

please note that the engine can only be stopped by disconnecting the battery!

The ignition circuit - hardness test

The best way to check whether an ignition system

is "overall intact" is with a spark gap. The breakdown limit for dry

air is around 3 kV per millimeter. A U-shaped plastic plate and a plastic

clothes peg are used to fix the ignition cable that has been detached from the

spark plug connector. The copper core must be flush with the cut surface of the

ignition cable insulation, if this is not the case, the ignition cable must be

shortened by 2 ... 3 mm with a "fresh" cut. The counter electrode

made of solid copper wire is screwed directly onto the upper plug contact with

an M4 nut (see Figure A.4-5).

We start with 2mm clearance and get the engine

running. If the spark gap does not break through, something is wrong. It should

be possible to increase the distance up to 5 mm (corresponding to 15 kV) without

the motor running unevenly. The test ETZ150 was still running at a distance of

10.5 mm!

Fig. A.4-5:

Estimation of the maximum ignition voltage

with a test spark gap

Safety note: In particular, people with health problems are

strictly discouraged from performing the test in this way. With modern,

high-energy ignition systems, an accidental sparkover on a part of the body can

be life-threatening.

B

Three-phase generator and 12 V electrical system

B.1 Field-regulated three-phase alternator for 12 V

vehicle electrical system

B.1.1 Checking the winding resistances

Fig.

B.1-1: Block diagram

of the 14V / 15A three-phase LiMa and voltage

a LiMa

phase in relation to crankshaft rotation

The stator and rotor

windings are designed in such a way that 4 full sine periods are generated on

each of the phases U, V and W per crankshaft revolution (see diagram in Figure

B.1-1). This relationship is important for the signal generation of electronic

tachometers, which are clamped to a phase line of the LiMa.

A very simple check of the windings of the rotor and stator was

described in [7 [ . Apart from a light bulb 12V / 21W, no further

measuring or testing equipment is required. This method may be used in vehicles

with conventional plus-regulating electromechanical or electronic controllers,

but not in on-board power systems with minus-regulating regulator circuit L9480

(see also Section B.4.3).

a) Switch the test lamp

between terminal 51 on the controller (= positive pole of the battery) and the

DF cable disconnected from the controller, test lamp lights up (compared to

step b)) with reduced brightness. If not, possible causes of error: Si

defective, DF cable interrupted, carbon brushes defective, field (rotor)

winding interrupted.

b) Connect the test lamp between 51 on the controller and ground. Test

lamp shines brighter than in step a). If not, there may be a short to ground in

the DF cable or in the rotor.

c) Disconnect cables U, V, W from the rectifier. Switch the test lamp

between 51 and one after the other against the cable ends U, V, W. Lamp stays

dark. If not, there is a short to ground in the stator winding or in the supply

lines.

d) Connect cable U to 51 on the controller. Switch the test lamp between

V and earth and between W and earth, the test lamp lights up. If not, the

stator winding or the supply lines U, V, W have an interruption.

More precise information

can be obtained by measuring the resistance directly on the

alternator (for setpoints, see Table B.1-2). These should generally be carried

out before the LiMa is tested with the engine running according to B.1.2.

|

element |

Measurement conditions |

Measurement between |

resistance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Three-phase windings |

Cable at U, V, W removed |

U and V V and W W and U |

0.32 Ω each according

to [7] |

|

isolation |

dito |

U and ground V and ground W and mass |

each > 1 M Ω |

|

Field winding (Rotor) |

Cable removed from DF- and DF + Slowly turn the rotor 360 ° during the measurement |

DF + and DF- |

(4.2 ±

0.3) Ω according to [2] |

|

Field isolation |

dito |

DF and mass |

> 1 M Ω |

Table

B.1-2:

Winding and insulation resistances of the 14V / 15A three-phase LiMa

Since the

measurement of very small or very large resistance values harbors

particular risk of error, the instructions in Section V.3 must be observed.

A test object

measured 4.5 Ω for the field winding (rotor) . Depending on the state of wear,

everything between 4… 5 Ω should be okay. The insulation resistance was generally over 20 MΩ.

B.1.2

Alternators - function test

The cables U, V, W

and DF + disconnected from the LiMa must be secured against unintentional

contact.

As shown in Figure

B.1-3, three test lamps are connected directly to the LiMa plug-in contacts U,

V, W. The use of three 60 W headlight bulbs is only necessary if the maximum

power output of the LiMa is to be achieved. Otherwise, 3 x 21 W is sufficient

for the test. However, three lamps are essential.

Either the on-board

battery or an external power supply unit (at least 2 A) can be used as a 12 V

fixed voltage source to generate the excitation current.

Fig.

B.1-3: LiMa

test circuit with external excitation

As soon as the 21 W

lamp is connected to the positive pole of the 12 V on-board battery, it starts

to light up. The applied excitation current is about 1.3 A.

The engine is now

started normally with the battery ignition and the engine speed slowly

increased from idle speed until the AC voltage on the multimeter

(Select AC range!) Has

reached 12 V ~. All 3 lamps in strings U, V and W must shine equally brightly,

around 180 W are converted. If the 21 W incandescent lamp is removed, the 3

load replacement lamps go out regardless of the speed.

Caution: If the

speed is increased further, the voltage rises above 12 V ~ and there is a risk

that the light bulbs will burn out!

Image

B.1-4:

Practical implementation of the load equivalent circuit with three

H4 lamps screwed

onto a copper bar

B.1.3

The field winding fuse 2A "slow"

The field winding of

the 14V / 15A three-phase LiMa is protected with a 2 A fuse. In normal

operation, the field current remains mostly below 2 A. Depending on the field

winding resistance (4.3 ± 0.3 Ω ) and

on-board voltage (max. 14.2 V), peak values of 3.4 ± 0.2 A are

possible (e.g. with low speed and full load).

The 2 A fuse with

the property "slow" will usually withstand these short-term

overloads. However, if a fault occurs (e.g. a diode on the rectifier plate has

broken through, overload due to a severely discharged battery, short circuit,

etc.), which continuously demands the maximum field current, the fuse will blow

after a long time and protect the LiMa from further damage.

However, it is

obvious that in this context “good” (<2A) and “bad” (> 2A) are close to

one another. Even the wrong characteristic ("nimble") would probably

blow the fuse the first time it was exceeded. On the other hand, a fuse

value> 2 A would make the intended protective mechanism absolutely ineffective.

If the 2 A fuse blows frequently, the LiMa, rectifier, battery and on-board

network should definitely be subjected to a thorough check. But it is also

conceivable that the fuses used were not sufficiently “slow”.

Due to the high

operational reliability of the rectifier

plate (200 V

version), the protection could also be omitted entirely. To be on the safe

side, a 100 µF / 63 V capacitor should be provided as shown in Figure B.4-2.

B.2 rectifier block

B.2.1

Circuit

Function of the rectifier block

The diodes D1 to D6

form a standard three-phase, three-phase rectifier bridge , the AC

voltage inputs of which are the 3 generator phases U, V, W and

the DC voltage output of which is the D + connection.

When installed, D +

is looped over the controller and the fuse and thus directly connected to the

positive pole of the battery. In addition to the task of AC voltage

rectification, the diodes D1, D3, D5 must also serve as reverse current diodes,

i.e. even if the generator voltage is zero at standstill, the battery cannot

reverse discharge via the three three-phase windings, because D1, D3, D5 then

block.

However, this is

also the reason that the controller does not have any useful information about

the current generator voltage at D +, because the battery voltage is always

present there, even when the engine is not running.

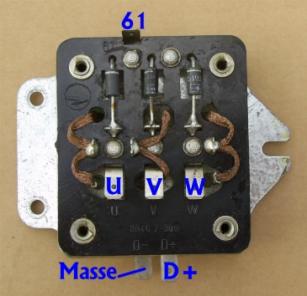

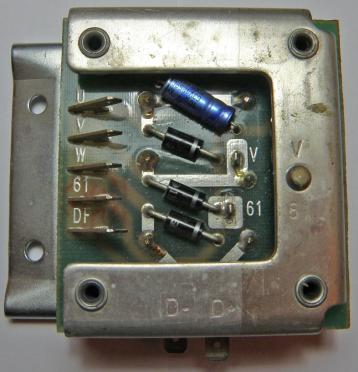

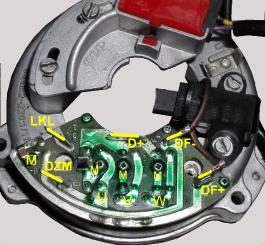

Image B.2-1: Rectifier block (left) and equivalent circuit

(right)

In order to obtain a

rectified voltage that corresponds to the current generator voltage, an additional

rectifier circuit consisting of D7, D8 and D9 leading to connection 61 is

required. There the speed- and load-dependent, rectified generator voltage can

be tapped, the size of which is decisive for the controller for controlling the

excitation current.

As a result, it is

not the voltage at D + that is the controlled variable, but the voltage at

connection 61. This leads to effects such that a load or temperature-related

voltage change at diodes D1, 3, 5 from diode trio D7, 8, 9 at 61 hardly "noticed" and therefore not

corrected. This fact must also be taken into account when troubleshooting. The

controller is not always defective if the voltage values on the

battery are not correct. The rectifier must always be included in the error

analysis.

Dielectric strength of the diodes

The first rectifier modules up to 1986 [2]

contained type SY170 / 1 and SY171 / 1 diodes with only 100V blocking voltage,

so that voltage peaks in the on-board network had to be suppressed with an

additional 2.5 µF capacitor.

The more voltage-resistant variant can be

recognized by the sticker "UR = 200 V". If it has dissolved, you can

recognize them by the 200 V components SY170 / 2 and SY171 / 2. Unfortunately,

both variants have the same spare part number, namely 8046.2-300. If the plate is changed, it must be ensured that the

capacitor is present in the 100 variant. In the case of the 200 V rectifier

module, the capacitor can be removed, but it can also be left without affecting

its function.

It is easily possible to replace a defective

rectifier plate with a modern 3-phase rectifier block for 15 A or more and with

a blocking voltage> 200 V. The auxiliary bridge D7, 8, 9 must then also be

implemented, whereby its current load can be set to be significantly lower

(approx. 5 A).

B.2.2

Function test

The function test of the rectifier block when

it is not connected is limited to the individual test of all rectifier

diodes. Either you use the diode test function of the multimeter or you create

a continuity tester with simple means, as shown in Figure B.2-2.

(a) (b)

Image B.2-2: (a) Test in forward direction (lamp lights up), display: forward

voltage

(b)

Test in reverse direction (lamp does not light up), display: reverse current

|

|

A node |

K atode |

|

|

|

|

|

D1 |

U |

D + |

|

D2 |

Dimensions |

U |

|

D3 |

V |

D + |

|

D4 |

Dimensions |

V |

|

D5 |

W. |

D + |

|

D6 |

Dimensions |

W. |

|

D7 |

U |

61 |

|

D8 |

V |

61 |

|

D9 |

W. |

61 |

Table B.2-3:

Allocation of the diode connections

In principle, transmission (lamp must light) and

blocking behavior (lamp remains completely dark) must be checked.

The forward voltage (= forward voltage) of each

diode is (0.85 ± 0.15) V at approx. 1 A forward

current (slightly dependent on the battery condition and the power consumption

of the bulb used). The reverse current must be well below 1 mA, typically in

the µA range.

B.3

Electromechanical controller (12V)

B.3.1

Mechanical adjustment

The mechanical adjustment of the 12 V

controller differs in the following points from that of the 6 V controller described in Section A.2.1:

The so-called current limiting contact

is located at the place of the reverse current contact .

According to [2], the contact distances are

Current

limiting contact 1.5 mm

Regulator

contact 0.3 mm

B.3.2

Electrical adjustment

As already explained

in section B.2.1 on the rectifier block, the controller input (61) and the

on-board power supply (51 / D +) must be galvanically isolated from each other

in the 12 V three-phase system, since the Battery voltage is present.

Fig.

B.3-1: Electrical function diagram of the electromechanical controller.

The main current

path from D + to 51 "winds" around the controller core with a large

cross-section only a few times. If the current in the main current path is too

high or if there is a short circuit, the few windings cause the current limiter

contact to open. If the current limiter opens, the field winding can no longer

be supplied with the maximum voltage from 61, but at most via the field winding

series resistor. This at least prevents extreme overloading of the LiMa in the

event of a fault (Fig. B.3-1).

The coil-resistor

combination parallel to the voltage winding is probably a device for

temperature compensation of the controller.

Connection sequence of the electromechanical 12

V regulator:

Ground DF 61 D + 51 ground

Preliminary test of the controller

with the help of resistance measurements

(unused connections remain open)

Before the measurement,

the contacts must be cleaned with a strip of hard, transparent drawing paper

(parchment), otherwise the small contact resistances of 0.4 Ω and less cannot be

detected!

|

element |

Measurement between |

condition |

resistance |

|

Voltage coil |

61 and mass |

|

R SSP (18 ± 2) Ω |

|

Current limiter contact and Controller contact together |

DF and 61 |

Rest position Current limit open Controller contact in Middle position |

0 ... 0.4 Ω R V (8.5 ± 2) Ω R V (8.5 ± 2) Ω |

|

Controller contact |

DF and mass |

pressed on Middle position Rest position |

0 ... 0.2 Ω R V + R SSP (26.5

± 4) Ω R SSP (18 ± 2) Ω |

|

Current winding |

D + and 51 |

|

0 ... 0.2 Ω |

Table B.3-2: Resistance values

on the 12 V

regulator

Electrical adjustment of the

controller

In contrast to the 6

V controller, general operating parameters are given for the 12 V controller in

[2] that can only be checked when installed and with the engine running (see

Table B.3-3).

As with the 6 V

system, concerns about the upper limit of the on-board voltage of 14.6 V (=

gassing limit of the battery at 25 ° C) must be reported, especially since the

voltage information relates to an unspecified point in the on-board network,

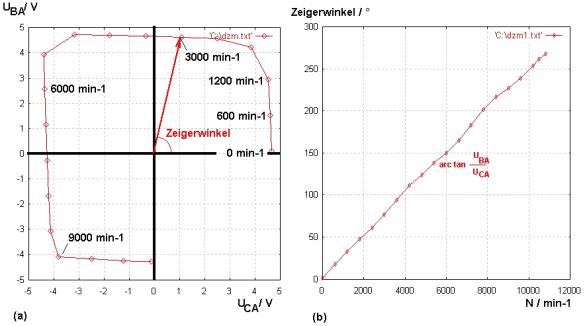

i.e. possibly can also refer directly to the battery terminals.